Syncope Evaluation in Cardiac Patients: Case Studies of Management

M3 India Newsdesk Apr 10, 2024

The article emphasises the complexity of diagnosing syncope, stressing thorough assessment and the importance of recognising high-risk features for appropriate intervention, illustrated by a case of vasovagal syncope progressing to cardiac arrest.

Syncope is a symptom. It is defined as a transient, self-limited loss of consciousness associated with loss of postural tone. The onset of syncope is relatively rapid and the subsequent recovery is spontaneous, complete, and relatively prompt. The underlying mechanism is a transient global cerebral hypoperfusion.

Types of Syncope

- Vasovagal syncope (also called neurocardiogenic syncope). This is the most common type of syncope. Around half of syncope instances are of the vasovagal variety.

- Situational syncope (a type of vasovagal syncope).

- Postural or orthostatic syncope (also called postural hypotension).

- Cardiac syncope.

- Neurologic syncope.

- Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome (POTS).

- Syncope with an unknown cause.

Syncope mimics

- Cataplexy

- Drop attacks

- TIA of carotid origin

- Falls

- Psychogenic pseudosyncope

History and physical examination

- In the elderly history of chest discomfort on exertion and breathlessness along with risk factors of CAD should be explored.

- Family history is of paramount importance: Burgada, HCM, LQTS, SQTS, ARVD.

- Past history of similar or recurrent events, any triggers (exertional events are more likely cardiac).

- Position of event: Neutrally mediated syncope is unlikely in supine patients.

- LVOTO-related syncope is exertional or just after exertion.

- Premonitory symptoms of nausea and impending fall after emotional or physical stress could be neutrally mediated syncope.

- Physical examination for a carotid bruit, S3 and S4, ESM for HCM, AS and MVP along with dynamic auscultation. Postural variation in BP including evaluation for POTS. All peripheral pulse examinations to exclude Takayasu arteritis.

Lab evaluation of syncope

“Routine” testing

- Complete blood cell count

- Electrolytes

- Blood glucose

- Electrocardiography

“Elective” testing

- Echocardiography

- Holter monitor

- Ambulatory continuous blood pressure monitor

- Portable event recorder

- Implantable loop recorder

- Tilt-table testing

- Electrophysiologic testing

- Neurologic testing

- Autonomic testing

- Electroencephalography

- Ophthalmography

- Carotid ultrasonography

- Transcranial Doppler ultrasonography

- Computed tomography

- Magnetic resonance imaging

- Endocrinologic testing

- Serum catecholamines

- Urine metanephrines

- Other cardiac testing

- Treadmill exercise test

- Coronary angiography

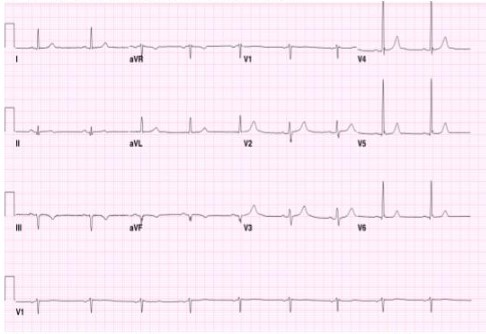

Role of ECG

A baseline ECG can often uncover underlying causes such as:

- Complete heart block (CHB)

- High-grade atrioventricular (AV) block

- Brugada syndrome

- Arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia (ARVD)

- Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM)

- Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome (WPW)

- Sinus pauses

- Trifascicular block

- Prolonged QTc intervals

Red flags in syncope

- Syncope resulting in injury

- Syncope during exercise

- Syncope in the supine position

- Suspected or known structural heart disease

- ECG abnormality

- Pre-excitation (WPW)

- Long QT

- Bundle-branch block

- HR<50 bpm or pauses > 3 seconds

- Mobitz I or more advanced heart block

- Documented tachyarrhythmia

- Myocardial infarction

- Family history of sudden death

- Frequent episodes (>2 per year)

- Implanted pacemaker or defibrillator

- High-risk occupation (bus driver, pilot etc.)

Low-risk characteristics include:

- Age <40 years;

- Syncope episodes happen while standing, transitioning from lying or sitting positions; experiencing nausea or vomiting prior to syncope; feeling warmth before fainting; syncope is triggered by painful or emotionally distressing situations, as well as by coughing, defecation, or urination; and

- A lengthy history spanning years of syncope exhibiting consistent characteristics similar to the present episode.

Clinical pearls

- Classical orthostatic hypotension is defined as a sustained decrease in systolic BP ≥20 mm Hg, diastolic BP ≥10 mm Hg, or a sustained decrease in systolic BP to an absolute value <90 mm Hg within 3 minutes of active standing or head-up tilt of at least 60 degrees.

- Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome patients, mostly young women, present with severe orthostatic intolerance (light-headedness, palpitations, tremor, generalised weakness, blurred vision, and fatigue) and a marked orthostatic heart rate increase (>30 bpm, or >120 bpm) within 10 minutes of standing or head-up tilt in the absence of orthostatic hypotension.

- In vasovagal syncope, the BP drop starts several minutes after standing up and the rate of BP drop accelerates until people faint, lie down, or do both. Hence, low BP in orthostatic vasovagal syncope is short-lived. In classical orthostatic hypotension, the BP drop starts immediately on standing and the rate of drop decreases, so low BP may be sustained for many minutes. Low heart rate with low BP happens only in vasovagal syncope which explains accelerated fall causing syncope in contrast to orthostatic hypotension.

- Autonomic function testing should be performed by a specialist trained in autonomic function testing and interpretation. The required equipment includes beat-to-beat BP and ECG monitoring, a motorised tilt table, 24-hour ambulatory BP monitoring devices, and other specialised equipment, depending on the range of testing.

- During the Valsalva manoeuvre, the patient is asked to conduct a maximally forced expiration for 15 seconds against a closed glottis, i.e., with a closed nose and mouth, or into a closed loop system with a resistance of 40 mm Hg. The hemodynamic changes during the test should be monitored using beat-to-beat continuous noninvasive BP measurement and ECG.

- During the deep-breathing test, the patient is asked to breathe deeply at 6 breaths per minute for 1 minute under continuous heart rate and BP monitoring. In healthy individuals, the heart rate rises during inspiration and falls during expiration.

- Autonomic function testing should be performed by a specialist trained in autonomic function testing and interpretation. The required equipment includes beat-to-beat BP and ECG monitoring, a motorised tilt table, 24-hour ambulatory BP monitoring devices, and other specialised equipment, depending on the range of testing.

- Carotid sinus massage (CSM) preferably is performed during continuous electrocardiogram (ECG) and noninvasive beat-to-beat blood pressure (BP) monitoring. Carotid sinus hypersensitivity is diagnosed when CSM elicits abnormal cardioinhibition (i.e., asystole ≥3 seconds) and/or vasodepression (i.e., a fall in systolic BP >50 mm Hg).

HUT

Indications for neurocardiogenic syncope include:

- Recurrent episodes of syncope in the absence of organic heart disease OR organic cause

- Unexplained single syncopal episode in high-risk settings (eg, occupational hazard)

- Older patients with unexplained falls

Relative contraindications to HUT:

- Proximal coronary artery stenosis

- Critical mitral stenosis

- Clinically severe left ventricular outflow obstruction

- Known severe cerebrovascular stenosis

Case illustration

- A 61-year-old gentleman presented with syncope. He was in the kitchen making dinner and developed lightheadedness. He sat on a step stool and the next thing he remember is being on the floor and his son calling his name. He felt like he couldn’t move. The kitchen was really hot and and he had missed lunch.

- Clinical examination was unremarkable.

- Discharged after 24 observations with a diagnosis of “Vaso-vagal syncope”.

- 3 months later.

- Cardiac arrest at home and successfully defibrillated but prolonged downtime.

- Had a slow neurologic recovery.

- ICD was implanted for secondary prevention.

Disclaimer- The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of M3 India.

About the author of this article: Dr Birdevinder Singh is a Senior Consultant Interventional Cardiologist at Patiala Heart Institute, Patiala.

-

Exclusive Write-ups & Webinars by KOLs

-

Daily Quiz by specialty

-

Paid Market Research Surveys

-

Case discussions, News & Journals' summaries