Cervical Cancer: Guidelines for Screening & Role of Vaccination

M3 India Newsdesk Mar 23, 2023

Cervical cancer is a leading cause of mortality among women. The screening methods for cervical cancer along with the latest guidelines issued by multiple organisations worldwide are penned down in this article.

In 2020, an estimated 604,000 women were diagnosed with cervical cancer worldwide and about 342,000 women died from the disease. The vast majority of these countries are in sub-Saharan Africa, Melanesia, South America, and South-Eastern Asia. India has reported around 21% of all cases in 2020.

Cervical cytology screening has been proven to decrease the incidence and mortality of cervical squamous cell cancer and to increase the cure rate of cervical cancer. High-risk groups include women without access to health care[2,3]. Risk factors include persistent infection with high-risk subtypes of human papillomavirus (HPV), such as HPV 16 and HPV 18 accounting for ~ 70% of cervical cancer.

Other risk factors are a history of smoking, parity, contraceptive use, early age of onset of coitus, a larger number of sexual partners, history of sexually transmitted disease, and chronic immunosuppression.

Methods of screening

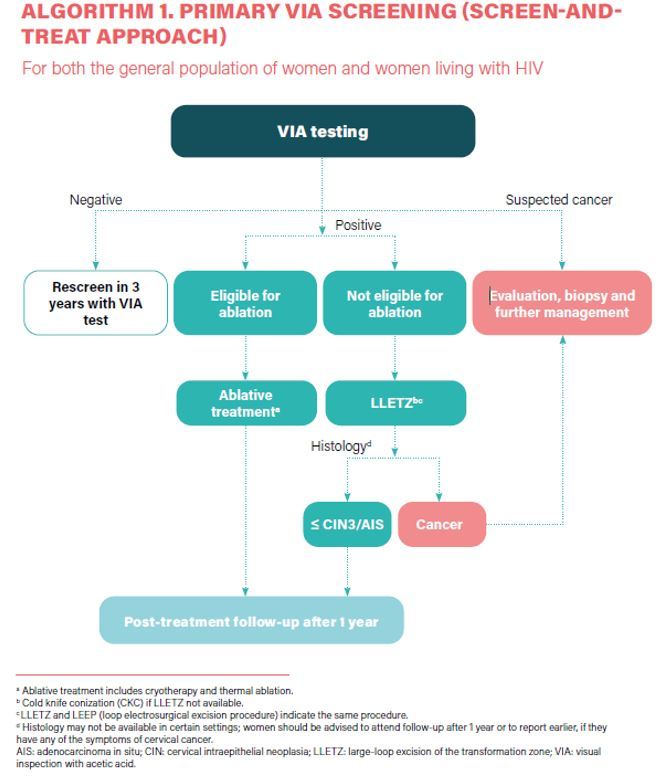

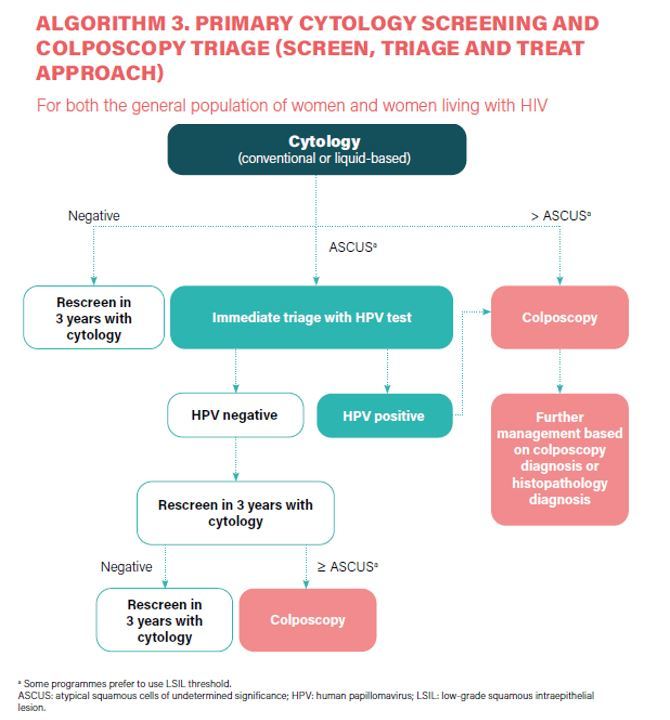

The traditional method has been cytology (the Papanicolaou test, also known as the Pap smear or smear test). When cytology results are positive, the diagnosis is confirmed by colposcopy, and appropriate treatment is informed by a biopsy of suspicious lesions for histological diagnosis. Newer screening tests introduced in the last 15yrs include visual inspection with acetic acid (VIA), and molecular tests, mainly high-risk HPV DNA-based tests,3 of which are suitable for use in all settings.

More recently, even newer tests and techniques have been developed

- Other molecular tests such as those based on HPV mRNA, oncoprotein detection or DNA methylation;

- More objective tests performed on cytological samples such as p16/Ki-67 dual staining; and

- More advanced visual inspection tests based on artificial intelligence/machine learning platforms (e.g. automated visual evaluation of digital images)

Abnormalities from cervical cytology testing range from the lowest to the highest risk of cancer as follows:

- An atypical squamous cell of undetermined significance (ASC-US)

- Low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (LSIL)

- Atypical squamous cell suspicion of high-grade dysplasia (ASC-H)

- HSIL

- Invasive carcinoma

Colposcopy and directed biopsies may be indicated for women with abnormal results. During a colposcopic examination, the cervix is viewed through a long focal-length dissecting-type microscope (magnification, 10x–16x). A 3% to 5% solution of acetic acid is applied to the cervix before viewing. The colouration induced by the acid and the observance of blood vessel patterns allow a directed biopsy to rule out invasive disease and determine the extent of preinvasive disease.

Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) is characterised by cellular changes in the transformation zone of the cervix. CIN is typically caused by infections with human papillomavirus (HPV).

CIN1 lesions are morphological correlates of HPV infections. CIN2/3 lesions are correlates of cervical pre-cancers that, if left untreated, may progress into cervical cancer.

Guidelines

Guidelines on cervical cancer screening have been issued by the following organisations:

- American Cancer Society (ACS)

- American Congress of Obstetrics and Gynecology (ACOG)

- American Society of Clinical Pathology (ASCP)

- American Society of Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology (ASCCP)

- U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF)

- World Health Organisation (WHO)

American consensus guidelines

In 2012, revised screening guidelines for cervical cancer and its precursors were developed and approved by the ACS, ASCCP, and ASCP. These new screening guidelines do not provide recommendations for populations at higher risk for cervical cancer, such as women who are immunocompromised (eg, HIV infection), were exposed to diethylstilbestrol in utero, or have a history of cervical cancer; more frequent screening may be appropriate for these patients. The panel consensus guidelines are widely accepted. The ASCCP updated their guideline for managing abnormal cervical screening tests and follow-ups in 2014. The USPSTF follows the same guidelines as issued by the panel.

|

Population( Age group) |

Screening Recommendations |

| <21 years |

Do not screen |

| 21-29 years | Perform cytologic testing alone annually |

| 30-65 years |

Perform cytologic and HPV co-testing every 5 years (preferred), or perform cytologic testing alone every 3 years (acceptable). |

| >65 years | Discontinue screening-if 3 consecutive negative cytologic tests or 2 consecutive negative contests in the past 1 year, with the most recent test in the past 5 years and if there is no history of HSILc, adenocarcinoma in situ, or cancer. |

| Women who have undergone hysterectomy | Discontinue screening |

Screening in abnormal cases (newer recommendations):

- Conservative management for women aged 21 to 24yrs and pregnant.

- Although co-testing is not recommended in women aged 25 to 29yrs, HPV testing may be recommended for abnormal tests.

- Women > 65yrs continue screening if ACS-US, even if HPV-negative.

- Co-testing was used for follow-up.

ACOG guidelines for cervical cancer screening in HIV-positive women

- Screening < 21yrs.

- HIV-positive women <30yr: cytology testing 3yrly, if three consecutive normal annual cytology tests.

- ACOG recommends against co-testing for women younger than 30yr.

- Women with HIV who are 30yr of age or older can undergo either testing with cytology alone or co-testing with cytology and HPV testing; those with three consecutive normal annual cytology tests can then be screened annually, and those with one normal co-test result can also be screened annually.

WHO guidelines

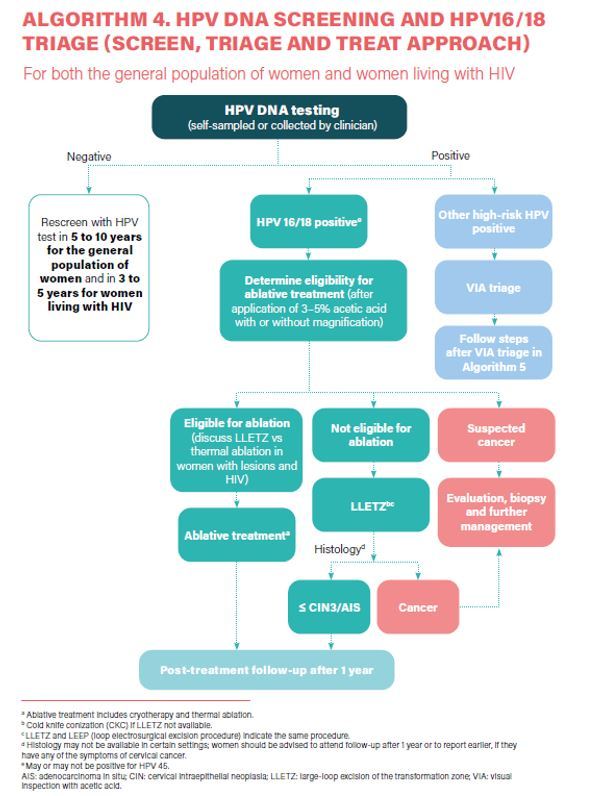

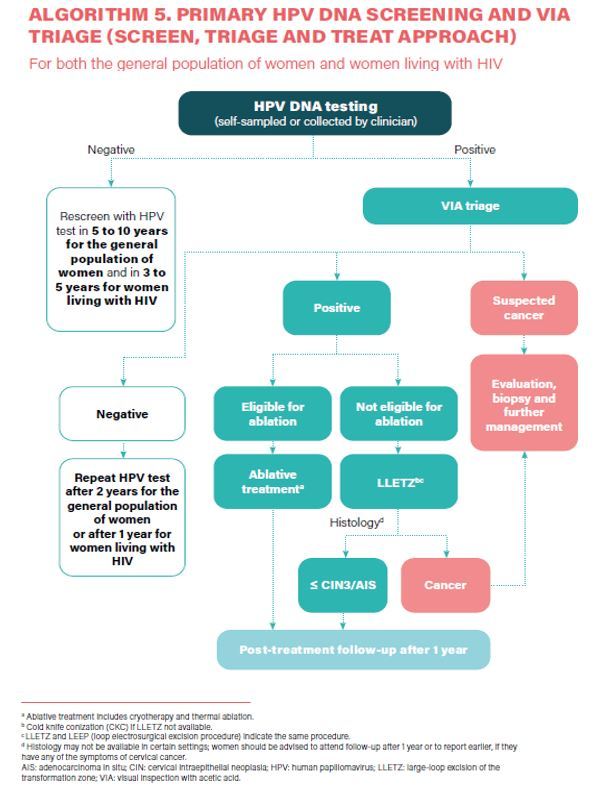

- HPV DNA detection as the primary screening test (Strong recommendation).

- HPV DNA primary screening test either with triage or without triage to prevent cervical cancer among the general population of women (Conditional recommendation).

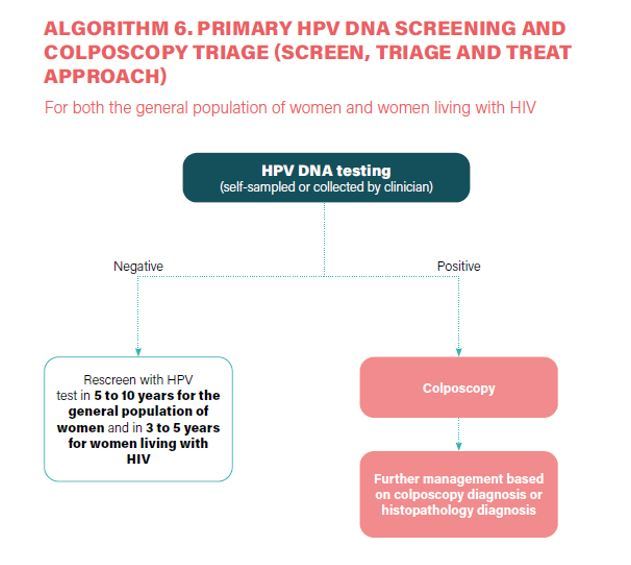

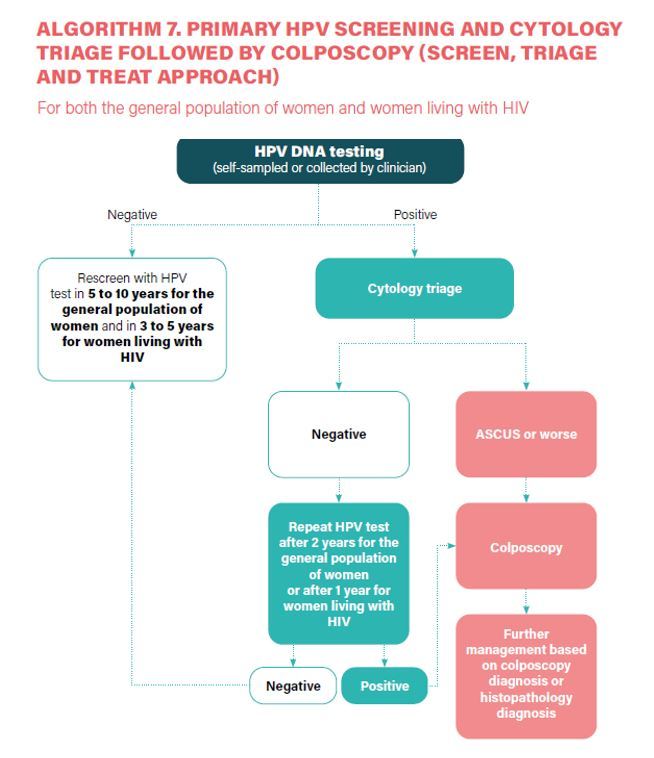

- a) In a screen-and-treat approach, WHO suggests treating women who test positive for HPV DNA. b) In a screen, triage and treat approach, WHO suggests using partial genotyping, colposcopy, VIA or cytology to triage women after a positive HPV DNA test (Conditional recommendation).

- Samples for HPV DNA testing must be taken by a healthcare provider or self-collected samples (Conditional recommendation).

- Regular screening from 30yrs (Strong recommendation).

- Stop screening after 50yrs, after two consecutive negative screening results (Conditional recommendation).

- Priority women 30–49yrs and 50–65yrs, never before screened.

- Screening interval - 5 to 10yrs with HPV DNA (Conditional recommendation).

- Where HPV DNA testing is not operational, regular screening interval 3yrs with VIA/cytology (Conditional recommendation).

- Women who screened positive for an HPV DNA test and then negative on a triage test are retested with HPV DNA testing at 24 months and, if negative, move to the recommended regular screening interval (Conditional recommendation, low-certainty evidence).

- Women who screened positive on a cytology test and then have normal results on colposcopy are retested with HPV DNA testing at 12 months and, if negative, move to the recommended regular screening interval (Conditional recommendation, low-certainty evidence).

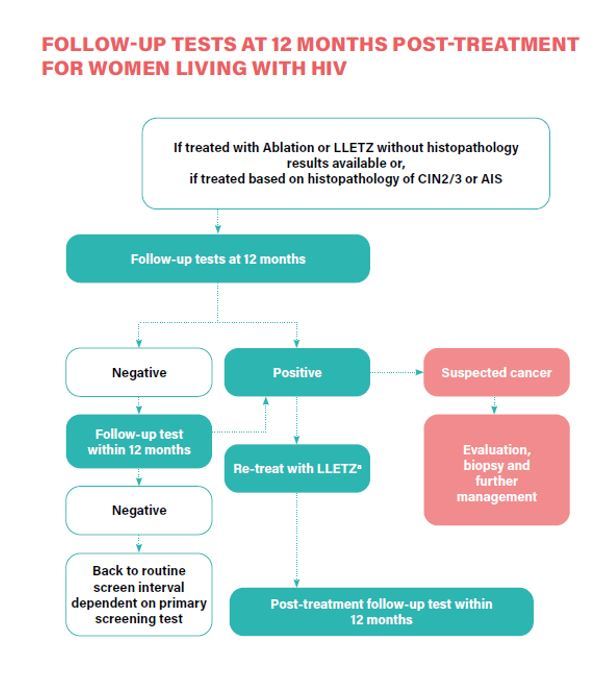

- Women who have been treated for histologically confirmed CIN2/3 or adenocarcinoma in situ (AIS), or due to a positive screening test are retested at 12 months with HPV DNA testing and, if negative, move to the recommended regular screening interval (Conditional recommendation).

Role of HPV vaccination

HPV 16 or 18 accounts for 66% of and the five additional types for about 15% of cervical cancers. The Advisory Committee on Immunisation Practices (ACIP) routinely recommends HPV vaccination at 11 or 12 years; vaccination can be given starting at 9 years. It is estimated that the implementation of this strategy could prevent 60 million cervical cancer cases and 45 million deaths over the next 100 years.

All HPV vaccines contain VLPs against high-risk HPV types 16 and 18; the nonavalent vaccine also contains VLPs against high-risk HPV types 31, 33, 45, 52 and 58; and the quadrivalent and nonavalent vaccines contain VLPs to protect against anogenital warts causally related to HPV types 6 and 11. Bivalent vaccines- Cervarix, Cecolin and Walrinvax. Quadrivalent vaccines – Gardasil, Cervavax. Nonavalent vaccine- Gardasil-9.

Vaccine efficacy and safety

Data were considered from 11 clinical trials of 9vHPV, 4vHPV, and/or 2vHPV in adults aged 27 through 45 years, along with supplemental bridging immunogenicity data. In per-protocol analyses from three trials, 4vHPV and 2vHPV demonstrated significant efficacy against a combined endpoint of persistent vaccine-type HPV infections, anogenital warts, and cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) grade 1 (low-grade lesions) or worse.

Prevalences of 4vHPV vaccine-type infection during 2013–2016, compared with those of the prevaccine era, declined from 11.5% to 1.8% among females aged 14 through 19 years and from 18.5% to 5.3% among females aged 20 through 24 years. In addition, declines have been observed among unvaccinated persons, suggesting protective herd effects.

A meta-analysis demonstrated that three doses of the bivalent (Cervarix) and quadrivalent (Gardasil) vaccines offered significant protection against cervical adenocarcinoma in situ associated with HPV16 and HPV18 among young women (aged 15–26 years): 88% (95%CI 30–98%). In a systematic review of RCTs, involving 13 753 females aged 16–26 years, there was little to no difference in efficacy against outcomes caused by the types contained in the respective vaccines between quadrivalent (Gardasil) and nonavalent (Gardasil-9) HPV vaccines. (OR 1.00, 95%CI 0.85–1.16)

Disclaimer- The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of M3 India.

About the author of this article: Dr Pradeep Jaiswal is a surgical oncologist from Bangalore.

-

Exclusive Write-ups & Webinars by KOLs

-

Daily Quiz by specialty

-

Paid Market Research Surveys

-

Case discussions, News & Journals' summaries