How to handle stroke emergencies

M3 India Newsdesk Dec 22, 2021

In this part of our series of emergency interventions, we discuss the salient clinical nuggets of the guidelines by the Directorate General of Health Services and the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare prepared for healthcare providers involved in the management of patients with stroke. The focus of this article is on the more common clinical questions faced in day-to-day practice.

Stroke is the second leading cause of death worldwide and was responsible for an estimated 6.5 million deaths and 113 million Disability-adjusted life years (DALY) in 2013. More than 2/3rd of these deaths occurred in developing countries. Recently, ICMR has come out with a report entitled 'India: Health of the Nation’s States', according to which stroke was the 4th leading cause of death and 5th leading cause of DALY in 2016. By 2050, more than 80% of the predicted global burden of new strokes of 15 million will occur in low and middle-income countries. In India, studies estimate that the incidence of stroke population varies from 116 to 163 per 100,000 population.

The aim of the DGHS and MOHFW guidelines is to help doctors, at primary and secondary levels of the healthcare delivery system to make the best decisions for each patient, using the evidence currently available.

Early management of stroke and/or TIA

Patients who are first seen after fully resolved transient ischaemic attack (TIA) or rapidly resolving neurological symptoms, need a diagnosis to determine whether, in fact, the cause is vascular (about 50% are not) and then to identify treatable causes that can reduce the risk of stroke (greatest in first 2 to 14 days).

- Any patient who presents with transient symptoms suggestive of a cerebrovascular event should be considered to have had a TIA unless neuroimaging reveals an alternative diagnosis.

- All such patients except those with transient monocular blindness should be referred for the imaging of the brain, either CT scan or MRI with vascular imaging using CT angiography (CTA) or MR angiography (MRA) or carotid ultrasound.

- Patients presenting with transient monocular blindness (amaurosisfugax) must have a complete ophthalmological examination to exclude primary disorders of the eye before diagnosing TIA.

- All patients with the diagnosis of TIA should be started on aspirin 150 mg daily and clopidogrel (300 mg loading dose and 75 mg daily dose) for the first three weeks followed by either aspirin 75 mg daily or clopidogrel 75 mg daily and should be assessed as early as possible by a specialist physician.

- Patients with crescendo TIA (two or more TIAs in a week) should be treated as being at high risk of stroke and should be assessed as soon as possible within 24 hours.

- Patients who have had a TIA but who present more than one week after their last symptom has resolved should be assessed as soon as possible but not later than one week by a specialist physician.

- All patients with TIA should be managed promptly as indicated on the lines of secondary prevention.

- “Dekhna, dikhana, hath, paer, bol, chal”- could be an easy mnemonic. Any sudden onset disturbance in dekhna, dikhana, hath, paer, bol or chal should raise suspicion of a cerebrovascular event and may indicate prompt medical consultation.

- Another commonly used acronym for stroke is FAST (F- Face drooping, A- Arm numb/weak, S- Speech slurred, T- Time). Time should not be wasted, and it is important to act fast for the treatment.

Management of established acute stroke care

The aim of the emergent evaluation is to:

- Distinguish stroke (a vascular event) from other causes of rapid-onset of neurological dysfunction (stroke mimics)

- To determine its pathology (haemorrhage versus ischaemia)

- Obtain clues about the most likely aetiology

- Predict the likelihood of immediate complications

- Plan appropriate treatment

It should be recognised that ‘stroke’ is primarily a clinical diagnosis and that the diagnosis should be made with special care in the following cases:

- In the younger generation

- If the sensorium is altered in the presence of mild to moderate hemiparesis

- If the history is uncertain, or,

- If there are other unusual clinical features such as gradual progression over days, unexplained fever or papilloedema

The management of acute stroke care includes:

Admission to the hospital- Most patients with acute stroke should be admitted to a hospital to:

- Perform urgent CT scan of the brain

- Detect worsening and perform urgent intervention and management

- Evaluate, monitor, and control risk factors for haemorrhage and ischaemia

- Prevent and treat non-neurological complications like aspiration pneumonia

- Plan rehabilitation

- Educate the caregiver

Generally, patients with acute stroke (onset within the last 72 hours or altered consciousness due to stroke), should be admitted to the hospital for initial care and assessment. Circumstances where a physician might reasonably choose not to admit selected patients with stroke include the following:

- Individuals with severe pre-existing irreversible disability (e.g. severe untreatable dementia), or terminal illnesses (e.g. cancer), who or whose caregivers opt to be cared at home or at a lower level healthcare facility. They may be treated for general conditions like diabetes, hypertension and any other comorbidity.

- Alert patients with mild neurological deficits (not secondary to ruptured saccular aneurysm) who present more than 72 hours after onset of symptoms, who can be evaluated and treated expeditiously as outpatients, and who are unlikely to require surgery, invasive radiological procedures, or anticoagulation.

Stroke unit- There is strong evidence to support a geographically defined (minimum four beds) unit in the hospital where patients with stroke are managed by a multidisciplinary team (minimum two physicians/doctors trained in stroke care, four nurses and a physiotherapist) with written standard protocols.

History, physical examination and common investigations

- History should follow the usual routine. Special attention should be paid to:

- Time of the onset of symptoms

- Recent stroke

- Myocardial infarction

- Seizure

- Trauma

- Surgery

- Bleeding

- Pregnancy

- Vegetarianism and use of anticoagulation/insulin/antihypertensive

- History of modifiable risk factors like hypertension, diabetes, smoking, non-smoking tobacco use, heart disease, hyperlipidemia, migraine, and history of headache or vomiting, recent childbirth, and risk of dehydration

- Physical examination should be on usual lines with special attention to ABC (airway, breathing, and circulation), temperature, oxygen saturation, a sign of head trauma (contusions), seizure (tongue laceration), evidence of petechiae, purpura or jaundice, carotid bruits, peripheral pulses and cardiac auscultation.

- Glasgow coma scale (GCS) score (separately for eye-opening, best motor and best verbal responses) should be recorded for each patient.

- Validated stroke scales like the National Institute of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) may be used to determine the degree of neurological deficit.

- All patients should have neuroimaging including vascular imaging, complete blood count including ESR, blood glucose, urea, serum creatinine, serum electrolytes, ECG and transthoracic echocardiography (in cryptogenic stroke transesophageal echocardiography should be done). Selected patients may require markers of cardiac ischaemia, liver function tests, serum homocysteine, chest radiography, arterial blood gases, EEG, lumbar puncture, blood alcohol level, toxicology studies, or pregnancy test, anticardiolipin antibody. In patients with cryptogenic stroke, protein C, protein S, and anti-thrombin III should be tested three months after the onset of stroke.

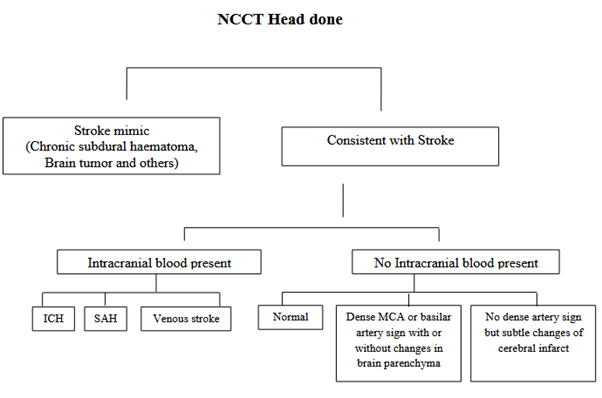

All patients should have their clinical course monitored and any patient whose clinical course is unusual for stroke should be reassessed for possible alternative diagnosis Brain imaging should be performed urgently in all patients with suspected stroke to determine the type of stroke (ischaemic or hemorrhagic), rule out stroke mimics like chronic subdural haematoma, brain tumours and to plan for treatment.

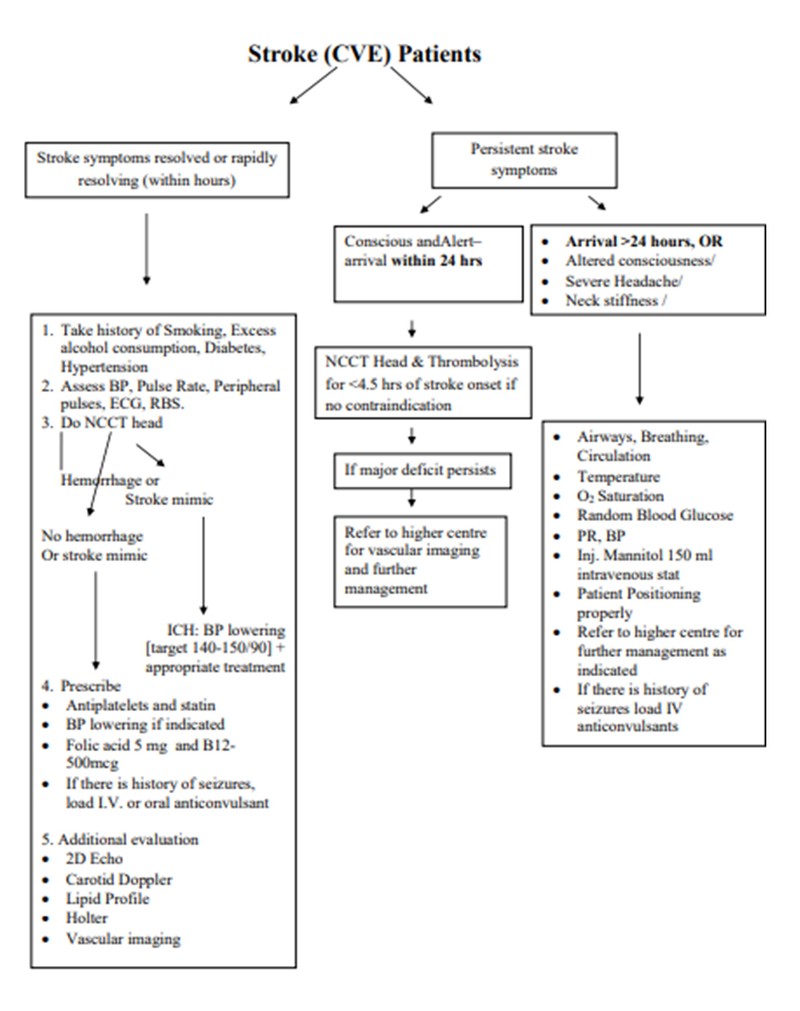

Algorithm for stroke patients at a district hospital

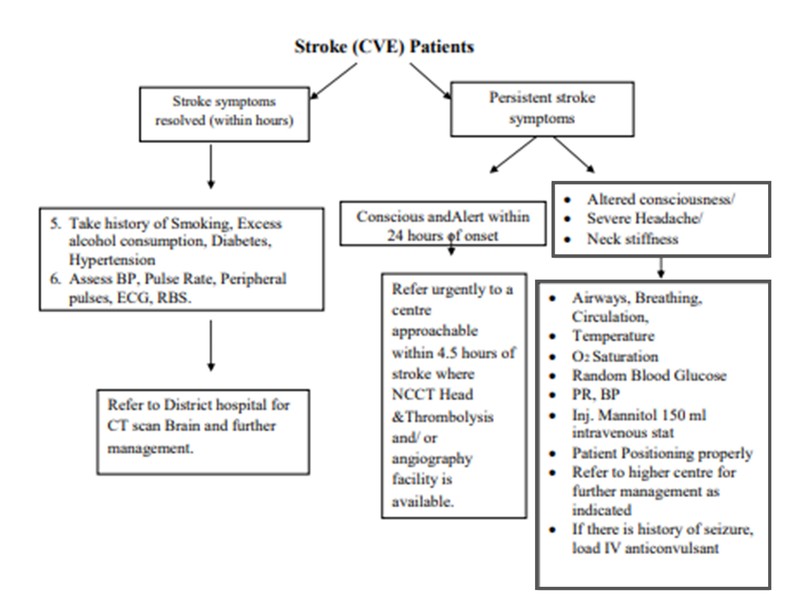

Algorithm for stroke patients at a primary healthcare centre

Immediate specific management of ischaemic stroke

- Immediate specific management depends on the time of arrival of the patients after the onset of symptoms and severity of stroke.

- All patients with a measurable neurological deficit after acute ischaemic stroke who can be treated within 4.5 hours after symptom onset should be evaluated without delay to determine their eligibility for treatment with a thrombolytic agent

- Patients with acute ischaemic stroke should be considered for combination intravenous thrombolysis and intra-arterial clot extraction (using stent retriever and/or aspiration techniques) if they have internal carotid or proximal middle cerebral artery occlusion causing a disabling neurological deficit and the patient can be referred to a tertiary healthcare facility, where the procedure can begin (arterial puncture) within 24 hours of last known well.

- Patients with acute ischaemic stroke and a contraindication to intravenous thrombolysis but not to thrombectomy should be considered for intra-arterial clot extraction (using stent retriever and/or aspiration techniques) if they have internal carotid or proximal middle cerebral artery occlusion causing a disabling neurological deficit and patient can be referred to a tertiary healthcare facility, where the procedure can begin (arterial puncture) within 24 hours of last known well.

- All acute stroke patients should be given at least 150 mg of plain aspirin immediately after excluding intracranial haemorrhage with neuroimaging (in patients receiving thrombolysis, aspirin should be delayed until after the 24-hour post-thrombolysis).

- Patients with acute ischaemic stroke who are allergic to or intolerant to aspirin should be given an alternative antiplatelet agent (e.g. clopidogrel).

- In patients with large hemispheric infarct [malignant middle cerebral artery (MCA) territory infarct], aspirin may be delayed until surgery. Aspirin may be started after a decision is made not to operate.

- In dysphagic patients, Aspirin may be given by enteral tube. For non-cardio embolic stroke, aspirin (at least 75 mg) should be continued as indicated in ‘secondary prevention'.

- Any patient with acute ischaemic stroke who is known to have dyspepsia with aspirin should be given a proton pump inhibitor in addition to aspirin.

- Patients with indications for neurosurgery should be referred to a centre with a neurosurgical facility.

- Indication of surgery for ischaemic stroke

- Patients with large middle cerebral artery infarct may be referred to higher centres equipped with provision for neurosurgery.

- Patients with middle cerebral artery territory infarction should be considered for decompressive hemicraniectomy and operated on as early as possible, preferably within 48 hours who meet the criteria below (the decision to be individualised):

- Decrease in the level of consciousness GCS score (total between 6 and 13, eye-motor score <9, motor score 5 or less), and

- CT scan showing signs of an infarct of at least 50% of the MCA territory, with evidence of midline shift >4 mm with or without infarction in the territory of anterior or posterior cerebral artery on the same side or diffusion-weighted, MRI showing infarct volume >145cm3.

- Patients with large cerebellar infarct causing compression of the brainstem and altered consciousness should be surgically managed with suboccipital craniectomy.

- Symptomatic hydrocephalus should be treated surgically with a cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) diversion procedure. Hemodilution therapy is not recommended for the management of patients with acute ischaemic stroke.

- No neuroprotective drug is recommended outside the setting of randomised clinical studies.

- Acute carotid or vertebral artery dissection

- Carotid or vertebral artery dissection should be suspected if the patient has neck pain, history of neck/neurotrauma or is young without any apparent risk factors.

- Any patient suspected of having arterial dissection should be investigated with appropriate imaging (brain MRI and MRA/CTA). People with stroke secondary to arterial dissection should be treated with either anticoagulants or antiplatelet agents. In selected patients, stenting may be indicated.

- In case facilities are not available at the centre, the patient may be referred to higher centres.

- Cardioembolic stroke

- Patients with disabling ischaemic stroke (i.e. large infarction) who are in atrial fibrillation should be treated with aspirin 150 mg for the first one to two weeks before starting anticoagulation.

- In patients with prosthetic valves who have to disable cerebral infarction and who are at significant risk of hemorrhagic transformation, anticoagulation treatment should be stopped for one week and aspirin 150 mg should be substituted.

- Heparin may be started within 48 hours of a cardioembolic stroke except in large infarctions. However, there is a lack of evidence to support this.

- In patients with suspected embolic stroke of undetermined source (ESUS), 24- to 48-hour Holter monitoring is indicated.

Immediate specific management of intracerebral haemorrhage (ICH)

ICH-related to anti-thrombotic or fibrinolytic therapy

ICH related to intravenous heparin requires rapid normalisation of a PTT by protamine sulphate with adjustment of dose according to the time elapsed since the last heparin dose (for <30 minutes: 1 mg per 100 unit of heparin; 30 to 60 minutes: 0.5 to 0.75 mg; for 60 to 120 minutes: 0.375 to 0.5 mg, for >120 minutes 0.25 to 0.3 mg/100 units of heparin).

Protamine sulphate is given by slow intravenous not to exceed 5 mg/min (maximum of 50 mg). Protamine sulphate may also be used for ICH related to the use of subcutaneous low molecular weight heparin.

- Monitor for signs of anaphylaxis. The risk is higher in diabetics who have received insulin.

- Follow-up with STAT a PTT every one hour for the next 4 hours, then every 4 hours through 12 hours of hospitalisation. ICH related to acenocoumarol/warfarin should be managed with vitamin K, fresh frozen plasma (FFP) and wherever available prothrombin complex concentrate (PCC).

- Vitamin K (10 mg IV) should be used but with FFP/PCC.Vit. K alone. It takes at least 6 hours to normalise the INR. FFP (15 to 20 ml/kg) is an effective way of correcting INR, but there is a risk of volume overload and heart failure. Both PCC and factor IX complex concentrate requires smaller volumes of infusion than FFP (and correct the coagulopathy faster but with greater risk of thromboembolism). For symptomatic haemorrhage after thrombolysis, administration of IV alteplase should be stopped if still infusing until NCCT head has been done. (If CT shows no evidence of bleeding, the infusion can be resumed).

- If the CT shows haemorrhage, then immediately check values of CBC, PT, a-PTT, platelets, fibrinogen and D-dimer. If fibrinogen is <100 mg/dL, then give cryoprecipitate 0.15 units/kg rounded to the nearest integer. Give 4 units of platelet-rich plasma if platelet dysfunction is suspected.

- If heparin has been administered in the past 3 hours, then follow the procedure given above on ICH related to heparin use.

- Serious extracranial haemorrhage should be treated in a similar manner. In addition, compressible sites of bleeding should be manually compressed.

- The patient should be referred to a neurosurgeon or vascular surgeon as needed for intracranial or extracranial bleeding respectively as needed.

Restarting Vitamin K antagonists (VKA)- For patients with a very high risk of thromboembolism (those with mechanical prosthetic heart valves), vitamin K antagonist therapy may be restarted at 7 to 10 days after the onset of the index intracranial haemorrhage. Those with lower risk may be restarted on antiplatelet therapy.

Indications for surgery in ICH

- Patients with cerebellar haemorrhage (>3 cm in diameter) who are deteriorating neurologically or who have signs of brain stem dysfunction should have suboccipital craniectomy and surgical evacuation of the hematoma.

- Patients with supratentorial ICH causing midline shift and/or herniation with impairment of consciousness or deteriorating neurologically should have a surgical evacuation of hematoma within 72 hours of the onset of symptoms unless they were dependent on others for activities of daily living prior to the event or their GCS is <6 (unless this is because of hydrocephalus).

- Patients with hydrocephalus who are symptomatic from ventricular obstruction should undergo a CSF drainage procedure.

Click here to see references

For the next part on General management of stroke, click here.

Disclaimer- The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author's and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of M3 India.

The author is a practising super specialist from New Delhi.

-

Exclusive Write-ups & Webinars by KOLs

-

Daily Quiz by specialty

-

Paid Market Research Surveys

-

Case discussions, News & Journals' summaries