Lung Cancer: The common clinical presentation and work-up for primary care: Dr. Ashok Komaranchath

M3 India Newsdesk Nov 18, 2020

This is the second article in the Lung Cancer Awareness series where Dr. Ashok Komaranchath provides an understanding of the most common clinical presentation of lung cancer in primary care.

Click to read other articles from Dr. Ashok Komaranchath.

We know that lung cancer is a deadly disease. One of the main reasons why it is so is because it is usually detected when it has already reached advanced stages. Nearly 40% of lung cancers in the developed world has metastasised, (reached stage IV) at the time of diagnosis. This figure is thought to be much higher in a developing country like India. Another 30% is detected at stage III.The below graph shows the dismal survival rates of lung cancer at these advanced stages.

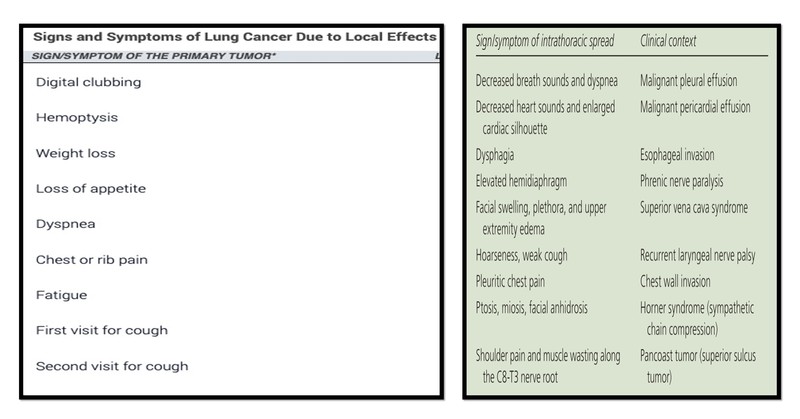

The clinical presentation is varied and can be divided into four broad groups. Symptoms caused by the primary tumour, due to intrathoracic spread, distant metastases and Para-neoplastic syndromes (PNS).

Common symptoms due to the primary tumour include cough, hemoptysis, dyspnoea and chest pain in decreasing order of occurrence. Intrathoracic extension may cause decreased breath sounds, decreased heart sounds, facial swelling and plethora, Pleuritic chest pain, hoarseness of voice, ptosis and/or mitosis, shoulder pain and/or muscle wasting along C8-T3 nerve roots.

A more detailed list with some clinical context is given below.(Table 1 & 2 : Latimer KM et.al.) Distant metastases may present with compromise of the affected organ.

The most common sites of metastases in lung cancer are the other lung, adrenal glands, bones, brain and liver. Hence, the symptoms may vary from severe bony pains to hormonal imbalances to severe headache and seizure from brain involvement.

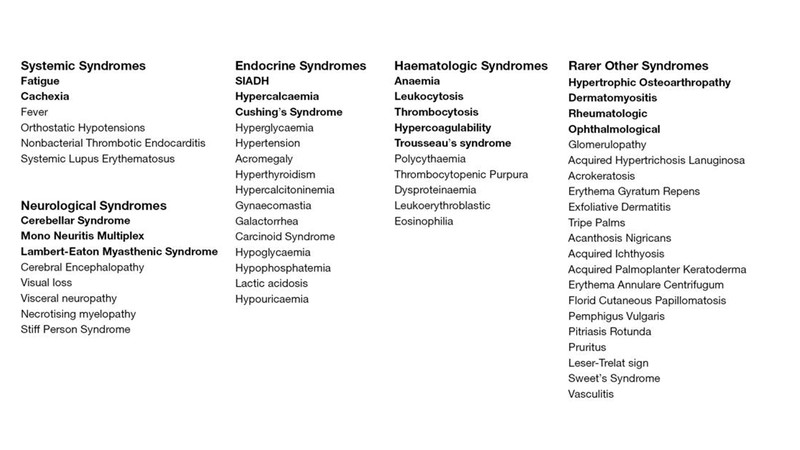

Paraneoplastic syndromes (PNS) are the most intriguing of symptoms thought to be an autoimmune reaction caused by antibodies secreted or induced by the lung cancer cells. Paraneoplastic Syndromes are again sub-classified into Endocrine, Neurological, Mucocutaneous and Hematological types.

Several cancers have the ability to produce more than one PNS and lung cancer is known to cause several of them, sometimes in the same patient. Some of the common ones include Syndrome of Inappropriate Anti-Diuretic Hormone (SIADH) secretion, Cushing’s syndrome, and Lambert-Eaton Myasthenic Syndrome (LEMS). The most classical sign of lung cancer, a sign that is regularly grilled into us since the first day of clinics; digital clubbing, is a poorly understood phenomenon with many hypotheses, one of which is that it too, is a paraneoplastic syndrome.

Table 3: List of paraneoplastic syndromes in Lung Cancer

Source: White J. ransl Lung Cancer Res. 2016

Hematology also plays an important role in the clinical picture of lung cancer, with the most common presentation being an anaemia of chronic disease. There may also be leucocytosis, thrombocytosis and in case of marrow infiltration by cancer cells, a full pancytopenia. Almost all cancers lead to a hyper coagulable state and may lead to thrombosis, DIC, acute coronary syndromes, CVA’s and superficial thrombophlebitis (Trousseau’s syndrome). As with the investigation of any medical condition, the best way to start is with a thorough history and clinical examination.

Useful clues as to the location of the disease, potential complications and sites of involvement may be elucidated with clinical assessment. It is at this point of time that smoking cessation (if the patient is a current smoker) should be offered. This is crucial as definitive studies have shown that quitting smoking, even in the face of a potential stage IV lung cancer has profound effects on the behaviour of the disease and the effectiveness of any form of therapy that is planned. Once a suspicion is raised, the most common primary investigation done in lung cancer is a chest X-ray. However, we also need to do all routine blood work as a part of workup and to prepare the patient for imaging and tissue biopsy.

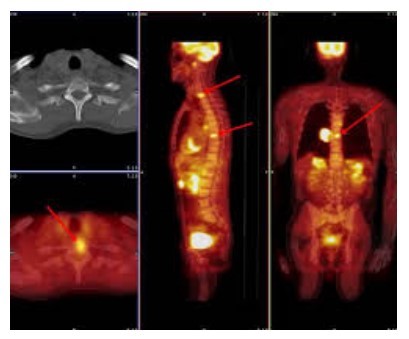

The most important imaging tool in recent times, especially in oncology is the PET-CT (Positron Emission Tomography) scan. It is a whole body scan that uses the concept that the most metabolically active and fast dividing cells (such as cancer cells) will need and utilise higher amounts of glucose than other tissues. A radioactive labelled glucose based contrast (18FDG - Fluoro-deoxyglucose) is given, which accumulates in tissues of high glucose utilisation. A major drawback of this system is that, the brain which uses the highest amount of glucose in our body per unit weight cannot be imaged clearly with this isotope.

Due to this flaw, and the fact that lung cancer often metastasises to the brain, a separate contrast MRI of the brain is indicated along with the PETCT scan as preliminary staging work up. Another flaw is the high dose of radiation delivered, which is, on average, 2-3 times what a contrast CT abdomen delivers.

Once we have the location of the primary within the lung and any evidence of local or distant spread, we must attempt to get a trucut biopsy of the cancer.It may be from the primary or any likely secondary lesion.

For example, if the primary is a deep seated hilar lesion near major vessels but a superficial supraclavicular lymph node is palpable, trucut biopsy or a whole node excision biopsy would be less risky and in fact, more informative about the tumour. In the event that the cancer has not spread elsewhere and is in stage III or less, we also offer a mediastinal staging. This is nowadays, most commonly done through bronchoscopy and Endo-Bronchial UltraSound (EBUS). An ultrasound probe at the tip of the bronchoscopy gives us a clear view of all mediastinal and hilar lymph nodes and also allows us to sample any nodes that look suspicious for malignant involvement.

Previously, we only needed to know if the tumour was malignant and if it was a small cell (SCLC) or non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). With the advent of advanced pathology and molecular biology as mentioned in the previous article, there are a vast gamut of tests that need to be performed to individualise and tailor treatment. Once the specimen is confirmed to be a non small cell carcinoma, specialised tests called immunohistochemistry are done to subtype it into adenocaricnoma, squamous cell or large cell carcinoma.

There are over 50 different mutations with varying implications discovered in lung cancer alone. Some of them are called targetable mutations, which means that there are drugs, either in the market or under clinical trials which have a therapeutic effect against those specific mutations. However, the current guidelines state that only 5 of these mutations are to be done on a regular basis at the time of primary diagnosis, which are; EGFR, ALK, ROS1, BRAF and PDL-1. All these have active, effective drugs which have not only brought down the use of intensive chemotherapy but also improved quality of life of the patients and sometimes even overall survival. As an example, EGFR was one of the first active ‘driver’ mutations to be described in NSCLC. Cancer mutations can be divided into primary ‘driver’ mutations and secondary ‘passenger’ mutations. Most cancers cannot form and some may not metastasise without certain specific driver mutations.

The severity, aggressiveness or pattern of spread may be influenced by secondary passenger mutations but they are not thought to be involved in the formation of the cancer per se. A drug was invented for patients with activating EGFR mutations, called gefitinib. It was found that gefitinib offered similar effectiveness and survival to patients with metastatic lung cancer patients who had this EGFR mutation at a fraction of the side effects that chemotherapy would cause.

Later generations of this drug have been released, with the latest one called osimertinib having been proven to be far more effective than chemotherapy with even lesser toxicity than the first generation gefitinib. The main drawback is that not all lung cancer patients have these mutations. The incidence of the most common mutation, which is EGFR is around 20% in westerners, between 30-50% in asians and less than 10-15% in smokers.

More about the treatment modalities according to each stage of the disease, will be discussed in the next article.

To read other articles in this series, click,

Lung cancer- Not a single disease: Dr. Ashok Komaranchath

Disclaimer- The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author's and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of M3 India.

The author, Dr. Ashok Komaranchath is a Medical Oncologist from Kerala.

-

Exclusive Write-ups & Webinars by KOLs

-

Daily Quiz by specialty

-

Paid Market Research Surveys

-

Case discussions, News & Journals' summaries